A Farm Project:

CHAMOMILE - GERMANby

Richard Alan Miller, c1999

Latin:

Matricaria recutita L. (formerly designated as Matricaria chamomilla)

Synonyms: German chamomile, Hungarian chamomile, wild chamomile, sweet false chamomile.

Life Zone: German chamomile does well in temperatures from 42 to 80 degrees F., with an annual precipitation of 15.5 to 56.0 inches and a soil pH of 4.8 to 8.3. It requires a sunny situation, and while the wild type flourishes in a rather dry, sandy soil, the double-flowered variety needs a richer soil and yields the heaviest crop of blooms in moist, stiffish black loam.

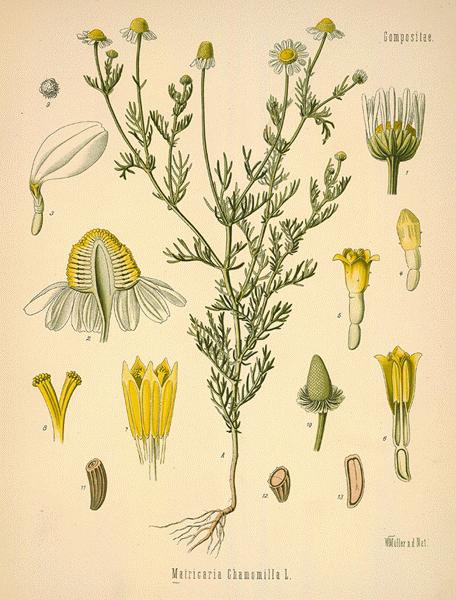

Description:

Much-branched annual herb, growing to 24 inches tall, with an aroma of pineapple; leaves twice or thrice pinnately divided into linear segments 1 to 2.5 inches long; flowers in solitary capitula about 1 in diameter, rays or a slight membranaceaous crown, without oil-glands. The flower heads appear singly at the ends of stems and branches.

The flowers are smaller than those of Anthemis nobilis L., the so-called Roman chamomile. Flowers May through October in Europe; March through April in Kashmir; May through October in North America. Chamomile thrives in temperate climates, but withstands considerable cold.

History:

German chamomile is one of the most favored medicinal plants in the world. In 1599, its blue essential oil was being recommended to treat colic. Today, chamomile is included in the pharmacopoeia of 26 countries throughout the world.

In Czechoslovakia, it is found in 32 commercially produced phytotherapeutical preparations and a variety of cosmetic products as a disinfectant, anti-inflammatory and sedative agent. Internally, infusions treat gastric diseases, urinary tract inflammation, and menstrual disorders. It is also used externally as a fomentation, inhalation or bath during inflammation of the muccosa or skin.

Native to Europe, though naturalized as a weed throughout North America. Chamomile has been cultivated in temperate countries including German, Hungary, Russia, Kashmir, Lebanon, Argentina and Colombia.

I conducted feasibility studies on chamomile in Grants Pass, OR. The crop did well and some experimental harvesting tests were conducted.

Chemistry:

Chamomile has a long history of pharmacological testing, starting when chamazulene (the blue compound in the essential oil) was shown to have anti-inflammatory action in the 1930's. The precursor of chamaxulene, the flavonoids, especially apigenin, have anti-spasmodic and anti-inflammatory activity. Later it was shown that alpha-bisabolol and bisabololoxides have similar activities. Therefore, essential oil compounds and flavonoids represent the main active principles.

A 1990 study of Della Loggia concluded that in terms of topical anti-inflammatory activity, matricin is much more effective than chamaxulene and alpha-bisabolol. A high matricin content is found in alcoholic tinctures and not in the steam distillate (essential oil), since chamaxulene is formed during distillation from matricin.

The most active compound was apigenin. A good quality extract contains all of the compounds like bisabolol derivatives, matricin and flavonoids. It is well known that chamazulene and bisabolol are very unstable and are best preserved in an alcoholic tincture. The same study showed that the essential oil exhibited the weakest inhibition of edema and that an alcoholic extract is better. The fresh plant extract was best and the dried plant extract was quite good.

According to studies by Holtzel, chamomile tea contains only 10 percent of the essential oil compounds and about 30 percent of the flavonoids. The quality of extracts also depends on the concentrations of alcohol since water increases the degree of enzymatic degradation. Optimum chamomile extracts in Germany contain about 50 percent alcohol. They are fairly stable and certainly better than a decoction (tea).

Nevertheless, some commercial preparations contain only traces of the active constituents. Guazulene is a compound that is as blue as chamazulene but less active. It can be synthetically prepared and therefore some companies adulterate their extracts with it to give them the blue color.

Apigenin is the most effective flavonoid compound. Aqueous extracts, such as a tea, contain quite low concentrations. Methanol provides the highest yield of apigenin glycosides. If you extract the same batch of chamomile with ethanol you get almost half the content. Using isopropanol, only a small part of flavonoids is extracted. Therefore, methanol would be the best choice, but due to the toxicological reasons, it can not be used.

Also, the water content of the solvent influences the extract's quality. The optimum is 50 to 70 percent alcohol to water, which gives you the highest amount of apigenin glycosides. With a higher water content, the apigenin glucoside decreases and apigenin increases because an enzyme becomes active that hydrolyzes the glucoside toward apigenin.

This takes place also during the drying process of chamomile flowers. A chamomile extract prepared from fresh flowers contains little or no apigenin.About 120 secondary metabolites have been identified in chamomile, including 28 terpenoids, 36 flavonoids. The essential oil content can reach from 0.2 percent to 1.05 percent in some polyploid varieties, up to 1.5 percent. Both alpha-bisabolol and chamazulene, considered the most bio-active, exhibit anti-inflammatory, antiphlogistic, antiseptic and spasmolytic effects. Alpha-bisabolol has become an important indicator of value.

Uses:

German chamomile is well-used in Europe, mainly for its anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic activity. Its indications for internal use are for gastric ulcers, gastritis, flatulence and peptic disorders. External use is also a very important area, with most commercial products used against inflammations and skin problems. It is very often used as a home remedy for inhalation to treat inflammation and infection of the respiratory tract.

The dried flowers are used in herb teas and in the manufacture of herb beers. The essential oils are used as agents in beverages, confections, desserts, perfumes and cosmetics.

The flowerheads contain an aromatic bitter principle (anthemic acid), which gives the drink a tonic effect, but may be emetic in large doses. Chamomile is also used in beverage form as a mild sedative, or "sleepy time" drink. Extracts of German chamomile have reported antiseptic, antibacterial and anti fungal properties. Externally, an infusion of the flowers or the oil has been used on contusions and other inflammation.

Internally, it serves as an anthelmintic, antispasmodic, carminative, diuretic, expectorant, sedative, stimulant and tonic. Externally, it is employed as a counterirritant liniment for bruises, hemorrhoids, sores. The active medical principle is chamazulene. Hot aqueous extract of the whole plant is said to cure tumors of the digestive tract.

Field Production:

Seedlings: Plants may be greenhoused, but direct sowing is best. In a pre-existing field, this annual will self-sow and produce seedlings very early in the spring (vigorous growth as early as February in southern Oregon). These seedlings would flower by the end of March, but unless moved into rows are not suitable for machine harvest. Self-sown seed is known as "meadow" or "field" chamomile. In northern Hemisphere, seed in fall and spring; Southern Hemisphere in March/April.Cultivation: Cultivated from seed, chamomile grows well in moderately heavy solid, rich in humus and rather moist, but will also grow in clayey soil, and even in sites almost depleted of soil and where little else will grow. It ranges from wet steppes to cool temperate through very tropic forest life zones.

Seeds may be broadcast or drilled (Brillion seeder). 0.3-lbs. is considered sufficient per acre. Seeding should be shallow in moderately rich, moist soil. About 8 weeks are required from seed to harvest, so that two crops a year can be grown in warmer climates. The short two-month growing season of German chamomile allows it to be inter-planted with other biennial herbs or planted as an early or late crop.

Direct sowing requires moisture conditions in the field which are very good, otherwise a poor and patchy germination is obtained. Nosti and Pardo (1967) observed that in spite of hazards from exposure, seed germination was much more abundant from superficial than from covered sowing, and the second year stand was dense as a result of self-sowing. In the transplanted crop the percentage of mortality is almost negligible.Dutta and Singh (1964) studied the effect of spacing on the weight of fresh flowers and oil yield of the crop with an erect growth habit. The highest yield of fresh flowers and oil content was obtained under 3 square-inch spacing.

Fertilization: The effect of nitrogen is very marked on the fresh flowers and oil yield, while that of P and K is negligible. Dutta and Singh (1961) observed that application of nitrogen, in form of ammonium sulfate at 36 pounds per acre significantly increased the fresh flower and oil yield of chamomile while the oil content itself was decreased significantly.

Irrigation: The crop is flood irrigated after transplanting, and at least 2 or 3 additional irrigation are required. Irrigation during the bloom period (March and April) is helpful as one additional flush is obtained and seed formation is delayed. On alkaline soils the crop is irrigated more frequently and about 6 or 8 irrigation are required during the crop cycle. Ketches (1966) observed that irrigation at the rosette stage increased yields substantially.

Weed Control: Though the Czechs have used Potalban, chemical herbicides affect the total oil content and composition of chamomile adversely. They do this by interfering with the metabolism of secondary products. Experimental results suggest that herbicides should be used with caution (and are not labeled for use). Therefore, weed or hoe manually at least twice to keep weeds under check.

Insects & Diseases: Chamomile is attacked by several nematodes; Root knot (Meloidogyne hapla and other species), Longidorus maximus and Heterodera marioni. It is parasitized by Cuscuta pentagona and Orobanche sp.

The following fungi are known to attack this plant: Albugo tragopogonis (White rust), Cylindrosporium matricariae, Erysiphe cichoracearum (Powdery mildew), E. polyphage, Helicobasidium purpureum, Peronospora leptosperma, P. radii, Phytophthora cactorum, Puccinia anthemedis, P. matricaiae, Septoria chamomillae, Sphaerotheca macularis (Powdery mildew).

Yellow virus (Chlorogenus callistephi var. californicus Holmes, Callistephyus virus 1A).

Foreign growers report the following as problems: aphids; white or cockafer grubs (Melolontha melolontha L.); meadow moth; Eupteryx atropunctuata; M. hippocastiani F.; Protomyces macrosporus Ung.; Chloridea (Heliotis) peltigera Schif.; and Albugo tragopogonis from Senecio squalidus.

Harvesting:

Traditionally in Eurasia, the flower heads have been harvested by hand when the plants are in full bloom. Tom Johnson (Buffalo, SD) and Harold Sipes (Phoenix, AZ) are both currently involved in R&D studies of mechanical harvesting techniques for chamomile. Northern Hemisphere harvests are in May/June; Southern Hemisphere is in October/November.

Harvest of the flower heads economically, with a low stem ratio is crucial to marketability. The flowers are small (3,600 to 4,000 heads per pound) and the plants have flowers at all stages of growth from bud to full bloom. Flowers are produced in flushes and four to five flushes occur in one season. The maximal yield is in the 2nd and 3rd flush. Peak production of bloom is 3rd week of March to the end of April.After harvest, the crop is allowed to stand. The remaining flowers mature and set seeds and are ready for harvest by May. In some cases, healthy, selected plants are allowed to mature and collect good quality seed.

Yields:

Yields of up to 400 pounds of dry flowers have been recorded in North American production. 5 pounds of fresh flowers yield 1 pound of air-dried flowers. Oil yields range from 0.25 percent to 1.35 percent, averaging 0.48 percent.

Drying:

Traditionally, the flower heads are spread thinly on canvas and sun dried. Grain dryers and other forms of forced, heated air (hop kilns) will work fine.

These flowers are delicate and should be dried with care. Mush (1977) observed that blowing dry air at a rate which removes 0.07 percent moisture per minute stimulated hydrolysis and increased evolution of ethereal oils in this crop.

Processing:

The harvested flowers are sifted in a suspended sieve (mesh diameter 7-11 mm), to separate the flower heads from the flowers with attached stems, and from clinging bits of weed or grass. Thus sifted, the flowers are spread out on the floor or on sheets, in thin layers, to dry.

The trade prefers the dried flowers packed in boxes or bales, not in bags since they prefer the unbroken condition.

Storage:

Should be stored indoors with cool temperatures and humidity. Protect from insects and rodent infestation.

Quality Control:

Stems should constitute not more than 10 percent of the product.

Ungrounded whole chamomile flower: The flower heads of chamomile are composed of a few yellowish orange to pale yellow ray florets and numerous somewhat darker disk florets on conical, hollow, receptacles, the latter from one to three inches in width. The disk florets are tubular, perfect and without a pappus. They ray florets are from 10 to 20 and have a 3-toothed and 4-veined, usually flexed pistillate corolla.

The involucre is hemispherical, composed of from 20 to 30 imbricated, oblanceolate, and pubescent scales. The peduncles are weak brown to dusky greenish yellow, longitudinally furrowed, more or less twisted, and attain a length of 1 inch. The achenes are somewhat obovoid and faintly 3 to 5-ribbed, with no pappus or only a slight membranous crown.

Powdered chamomile flowers are moderate yellowish brown to light olive-brown. It has a pleasant, aromatic odor and an aromatic and bitter taste. It shows numerous spinose, spherical or triangulate pollen grains with 3 pores and up to 25 microns in diameter, and

(a) fragments of corolla from ray florets with papillate epidermal cells; a few short glandular hairs;

(b) fragments of achene tissue with epidermal cells having scalariform markings or wavy longitudinal walls, and paenchyma containing rosette aggregates of calcium oxalate, the later up to 10 micros in diameter;

(c) fragments of characteristic tissue of anthers composed of elongated cells with scalariform walls;(d) fragments of stigmas, the upper end bearing porous fibers, tracheae, and elliptical stomata, the latter up to 30 micros in length.

Marketing:

German chamomile is the fifth top selling herb in the world. It is a major food, cosmetic and pharmaceutical additive. It is sold as either a flower head or as an oil, while Roman chamomile (Anthemis nobilis L. ) is sold exclusively as an oil. While world volumes are unknown, it is estimated at more than 50,000 ton annually.

German chamomile flower heads are used as a major tea flavoring ingredient (food market), a light sedative (pharmaceutical market), and as a pot pourri ingredient (floral trade). The oil is used extensively as a cosmetic ingredient, both as a conditioner and dye.

Current world sources of supply include Germany, Hungary, Russia, what remains of Yugoslavia, and now Argentina. The oil is produced in Germany, Hungary, India, and Greece. Egypt generally produces only Roman chamomile. None of these countries currently use automation for the harvest of flower heads.

Prices for German chamomile begin at $1.50 per pound for lesser grades and powder-fines, while most number one imports begin at $2.50 per pound, FOB NY. Premium grades can sell for up to $3.85 per pound. With the current trends in Europe, these prices should increase within the next two years. These prices should drop significantly with the development of a flower head harvester.

Fully developed flower heads are picked using various types of pickers (Czecho-Slovak types VZR-4,6). Flower heads are collected with a comb roller and moved by vacuum through tubes into trimmers. On level fields, the harvester captures 85 percent of the quality flowers. The fresh biomass is then sorted by machines into flowers, which are usually dried in hot-air dryers, and the remainder which is used to produce essential oil and water and alcohol extracts. The waste from extraction is mixed with livestock feed.

The crop is well-suited to North America, especially in regions like Montana where there is limited crop options and fairly hostile weather. Russia, for example, used most of its tundra-type soils to cultivate this crop. And while yields were low, they were still productive on lands not fit for grazing. With light irrigation, German chamomile could be grown on wheatland regions of North America.

What is needed to make this and many other crops feasible in the current market atmosphere of change is automation in the harvest of flower heads. The critical aspect is that no stem should remain on the flower. This causes a distinct change in flavor and is totally unacceptable in current markets. If you are a tinkerer, this could be the project of the decade.

CROP PROJECTIONS

FOR

FLOWER-HEAD PRODUCTS

by

Richard Alan Miller, c1999

The following projections have been made to determine the future economics in the harvest of flower-head products for the Herb & Spice trade. These are only estimates, based on 20 years of marketing these various crops. Some are nw products which have never been previously available except by hand harvests.

These projection indicate that more than 100,000 new acres of herb flower-head crops would be needed for full production by 1996, if a flower-head harvester was developed at this time. This type harvester would also make a number of new crops available for consumption.

I proposes a project to facilitate the development of a mechanical harvester for harvesting many types of herbal products. The project would involve building a modified header harvest system, attachable to a John Deer-type swather to sever flower-heads from the plant stems and collect them into mobil containers for drying and further processing.

Working with a marketing consultant (like Northwest Botanicals, Inc.), the harvested products should be evaluated for quality before and after processing. The harvester would provide a means of increasing the capacity of domestic growers to produce more of these products and do it more efficiently. Cheaper harvest costs, increased volume of production, and more consistent supplies available would allow North American growers to compete more favorably with imported products.

The primary tractor should be a John Deere-type of draper-swather, with a belt conveyor to deliver cut product to a wagon being pulled from behind. A used tractor like this should cost about $3,000, plus a second belt conveyor modification of $2,000. The wagons should cost about $500 each, and the farmer will need at least two.

Development of mechanical harvester for herb flowers is given as

It is now estimated that more than 40 units could be sold within the first two years of production, with another 50 to 100 units within 5 years. A typical pyrethrum farm of 5,000 acres might want 3 units for the harvest. Most individual chamomile growers will only farm up to 200 acres.

Vomel. A., Reichling, J., Becker, H., and Drager, P., 1977. "Herbicides in the cultivation of Matricaria chamomilla." I. Communications: Influence of herbicides on flower production and weeds (in German). Planta Med. 31: 378-389.

Maas, G., 1979. "Herbicide residues in some medicinal plants. Planta Med. 36: 251 (Abstr.)

Nagy, F., 1977. "Up to date weed control system in the large scale production of lavender, peppermint, tarragon and chamomile (in Hungarian). Novenyvendelem (Budapest) 13: 399-408. Wd. Ab. 27: 4081.

Reichling, J., Becker, H., and Drager, P.D., 1978. "Herbicides in chamomile cultivation. Acta. Hortic. 1978 (73): 331-338.

Roberts, H.A., and Riocketts, M.E., 1973. "Comparative tolerance of some dicotyletons to pronamide and chlorpropham." Pestic. Sci. 4: 83-87. FCA 26: 5218.

Vekshin, B.S., 1976. "Herbicides and the optimization of methods of cultivation of medicinal crops." Pharm. Chem. J. (Eng. Transl.) 10: 1655-1659. Translation of Khim. Farm. Zh. 10 (12): 78-82, 1976. WA 2228.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

For general information on additional books, manuscripts, lecture tours, and related materials and events by Richard Alan Miller, please write to:

OAK PUBLISHING, INC.

1212 SW 5th St.

Grants Pass, OR 97526

Phone: (541) 476-5588

Fax: (541) 476-1823Internet Addresses

DrRam@MAGICK.nethttp://www.nwbotanicals.org

http://www.herbfarminfo.com

also see the Q/A section of

http://www.richters.comIn addition, you can visit Richard Alan Miller's home page for a listing of his writings, also containing links to related subjects, and direction in the keywords Metaphysics, Occult, Magick, Parapsychology, Alternative Agriculture, Herb and Spice Farming, Foraging and Wildcrafting, and related Cottage Industries. Richard Alan Miller is available for lectures and as an Outside Consultant. No part of this material, including but not limited to, manuscripts, books, library data, and/or layout of electronic media, icons, et al, may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of Richard Alan Miller, the Publisher (and Author).